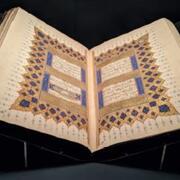

Mohsen Goudarzi, AM '14, PhD '18, heard the call of the Qur'an at a young age. Now, in his first year as Assistant Professor in Islamic Studies at HDS, he continues to delight in uncovering new understandings within the sacred text's complexities.

Growing up in Tehran, Goudarzi remembers listening to a young boy his age reciting the Qur'an on a nationally televised competition: "He was a virtuoso—it sounded so beautiful. And I knew that was something I wanted to do," he says. With his grandmother's encouragement, young Goudarzi delved into the techniques and grammar of Qur'anic Arabic, spending hours listening to and emulating professional Qur'anic reciters.

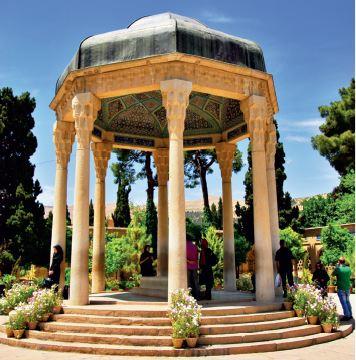

His curiosity didn't end there. As a teenager, Goudarzi immersed himself in literature—especially the poetry of popular Persian writers like Hāfez and Rūmī. He notes a similar literary quality in the Qur'an.

"The Qur'an is a poetic work. It tells us that it's not poetry. But it is very poetic. It rubs shoulders with poetry in a literary register. The beauty of the language and the recitations are part of what drew me to this text," Goudarzi says.

After high school, Goudarzi studied computer engineering, earning undergraduate and graduate degrees in the growing field—but kept finding himself drawn back to the humanities and religious history. To honor this lifelong passion, he decided to pursue a master of arts in religious studies from Stanford University. It was this pursuit that further developed his interest in multireligious education and ultimately brought him to Harvard.

Delight in Difference

At Harvard, Goudarzi admired the approaches of Professor Ali Asani, the late Professor Shahab Ahmed, and the late Professor Ahmad Mahdavi-Damghani, which underscored the diversity of the Islamic tradition—the many different centuries, geographic areas, and thinkers who have contributed to its rich tapestry.

He says two courses offered through HDS widened his academic interests, "Early Christian Texts: The Greek Tradition," with Professor Charles M. Stang, and "Introduction to the Hebrew Bible," with Professor Andrew Teeter.

Reading the Bible closely from literary and historical perspectives resonated deeply with Goudarzi, sparking a delight in multireligious education: "Many of the same concepts and concerns that we find in the Qur'an we also find in the Bible and related texts—in different ways, with different historical actors and contexts—but still so many overlaps. And what binds many Muslim, Jewish, and Christian readers of these ancient scriptures is that they are all trying to reconcile their experiences and theological commitments with belief in an omniscient and omnipotent God."

God Knows Best: Exploring the Mysteries of the Qur'an

Goudarzi's research focuses on the intellectual and social aspects of Islam's emergence and the ways Muslims have understood the Qur'an over the centuries.

"I'm trying to understand the Qur'an on its own terms as a text. But I'm also trying to understand some of the ideas that it raises or some of the debates it participates in, which can have long and tortuous genealogies."

What motivates him the most is solving some of the puzzles that still remain. Goudarzi says that there are many aspects of the Qur'an—like the mysterious letters that appear at the beginning of some of its surahs—that are not fully understood.

Goudarzi is currently writing a paper on a word in Surah 5 of the Qur'an that is used in an unexpected way: dīn, which is "generally understood as religion," appears in the middle of a passage discussing food prohibitions.

"It is surprising that this word appears there in the third verse. The verse lays out a list of food prohibitions, then declares the perfection of dīn, and again goes back to finish its dietary legislation by saying that in an emergency, people can eat the forbidden items. We think we understand the word, but maybe we don't because it appears in a context that doesn't make a lot of sense. I'm arguing that it doesn't mean religion exactly. It refers to serving God through cultic rituals, and if we recognize that, then it makes perfect sense why the word appears in that context. That's something that scholars of the Qur'an do often: we try to revisit some of the concepts that we think we have understood and argue that if we look at them in a new way, then we can make better sense of a certain passage or surah and understand aspects of its coherence that we didn't understand before."

That openness to greater understanding and multiple view points is also found in the Islamic exegetical tradition, which is characterized by "epistemic humility," Goudarzi says.

"There is not an urge to quickly close the door and say definitively 'this is what the text means.' There's this catch phrase in the commentaries: God knows best," Goudarzi says. "That's a phrase that oftentimes scholars will use to close a discussion. It's a way to say, 'I don't know. I'm just a mere mortal, and these are God's words. I don't want to say that this is what they mean exactly. God knows best."'

Teaching in a Multireligious Setting

As a professor, Goudarzi brings that humility into his classroom.

"If one is insistent on a very specific understanding of the text, then they risk closing the door on learning from other ways of looking," he says. "Each one of us brings a unique set of experiences, backgrounds, talents, and skills to the study of a tradition, text, or community."

His first class, Exploring the Qur'an, has already attracted a variety of students—Muslim, Jewish, Christian, Hindu, and a number of other faiths (including those who identify with multiple traditions or none at all).

"I couldn't have imagined a better cohort of students—hey were very generous with each other. Sometimes I felt that some non-Muslim students were looking at the Qur'an almost from the perspective of Muslims—trying to understand or empathize with how Muslims would look at the text—and vice versa."

In the classroom, Goudarzi brings comparative texts, as well as ideas from other traditions, to place the Qur'an within a broader context of religious history. He says it helps to underscore the complexity of the text itself and helps his students relate to the time period in which it was first promulgated.

"I think it's really important to maintain a balance between how the Qur'an has served as a cornerstone and a fountain of meaning for Muslims over the past 14 centuries—and how it is profoundly connected with the biblical tradition and the broader historical context of the late antique Near East."

As a scholar who has read the Qur'an in full countless times, Goudarzi delights in what new understandings his students can bring to the study of the text.

"What I tell all my students is: 'Do not think that because you are not experts in this tradition that you do not have worthy ideas to share. Each one of you is going to notice things that maybe no one else has seen before.'"

—by Suzannah Lutz, ALM '21

"The pen of creation did not go awry at all," proclaimed our master. Kudos to his pure and forgiving ("wry-covering") vision!

"I have never imbibed alcohol, but I wonder if the experience may be similar to reading the poetry of Hāfez—a kind of elation and intoxication. Poetry is something that you can find solace in from the outside world, from an economic meltdown or political instability. Hāfez himself was writing poems when much of the world around him was grappling with the consequences of the Mongol invasions, and Tamerlane's similarly disruptive conquests were underway. But when you enter his poetic world, it is incredibly serene. It's like you are walking in a beautiful, peaceful garden filled with delight. Hāfez in particular is a cherished poet dear to my heart."

—Mohsen Goudarzi on the power of Hāfez's poetry (excerpted above in Persian and English)